| HOME | NEWS | BIOGRAPHY | MUSIC | STAGE & SCREEN | GUESTBOOK | STUFF | GALLERY |

|---|

We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

TERRASCOPE 2010

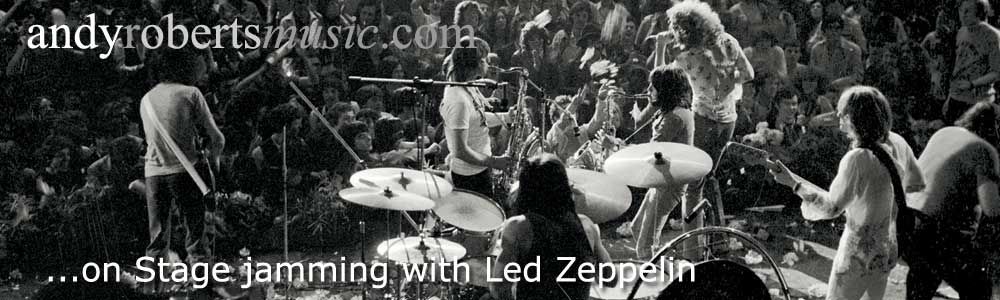

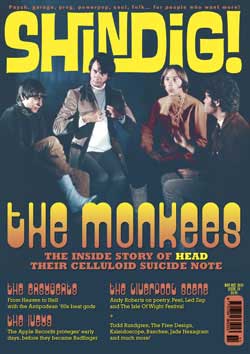

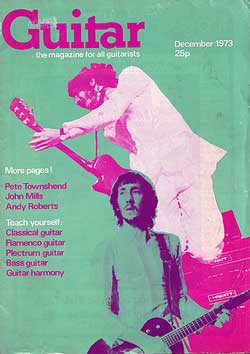

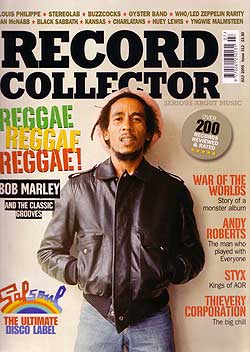

It’s been nearly 20 years since the Ptolemaic Terrascope cornered Andy Roberts at the Bracknell Folk Festival for a lengthy chinwag (originally published in PT13). Since then, he’s reunited with some of the Bonzos, overseen reissues of most of The Liverpool Scene’s back catalogue, released several albums with Plainsong (featuring Iain Matthews and Clive Gregson), guested on dozens of releases by everyone from Roy Harper and Dennis (Dr. Hook) Locorriere to Richard Thompson, Ashley Hutchings, Maddy Prior, and Kirsty MacColl - and supervised the reissues of his solo back catalogue, starting with his first two unforgettable albums and including a deluxe 2xCD anthology. Oh, and he also was a member of the “fake” Pink Floyd band on over a dozen dates of their classic The Wall Tour! So it seemed like another chat with Andy was long overdue, and Jeff Penczak caught up with him in the midst of his extremely busy schedule to discuss the solo years and catch up on what lies in wait for this extremely enigmatic and highly in-demand artist.

PT: Your solo debut, Home Grown was released right around the time of the last Liverpool Scene album. Were you recording them concurrently, and were any of the solo pieces originally planned for LS? AR: My best recollection is that the sessions for Home Grown took place in December 1969, pretty soon after Liverpool Scene got back from their US tour that fall. It was an entirely separate enterprise from the band, though it was steered by Sandy Roberton, who managed and produced the Scene. The only track which had its origin in the Liverpool Scene’s repertoire was The One-Armed Boatman And The Giant Squid, which was already appearing in the band’s set lists almost a year previously. The St Adrian Company album was recorded around six weeks later, in January 1970, I think. PT:It seems to take a kitchen sink approach, offering elements of country, folk, pop, even a nifty little jig. Were you intentionally laying all your musical cards on the table to reach as wide an audience as possible, or did you perhaps want to distance yourself from the Liverpool Scene material by showing your fans that you had a lot of musical tricks up your sleeve? AR: With the blinding clarity of almost 40 years’ worth of hindsight, I can state categorically that I haven’t a clue! It certainly seems the way you describe it. In all honesty, I didn’t really plan this album at all – I just set out to do songs which interested me, some of which, certainly, wouldn’t have been considered for Liverpool Scene gigs or recordings at that time. I wasn’t appearing solo much, if at all, at that time, so I just set out to record things I liked, with no overall concept for the album – I wouldn’t have understood that aspect of a record in those days. The fact is that the LS American tour had given us a severe kicking – we had lost what was at that time a substantial amount of money, the gigs had mostly been indifferently received, and, although we had enjoyed the experience, we were trying to come to terms with it all in a number of differing ways as individuals. Even when we had still been in the States, we disagreed as to how we should approach the business of fixing the problem of our lack of success. Adrian and Mike, who were both quite a bit older than I was, had a more laid back view – you could ask Mike how he felt, for instance – but I know how I saw it; I thought (at the time, though I cringe at it now!) that what was required was for me to be a desirable and credible object, both sexually and musically. I wore ever tighter trousers – so tight that if I’d farted I’d have blown my boots off, and tried to meet the gap in the tour material by writing songs like Human Tapeworm. This was because I was very impressed by some of the bands we had supported on the tour, like Steve Miller’s band, for instance, who we supported at the Boston Tea Party. I thought he was the full package – sexy, fun and musically brilliant – classic underground pop star stuff. And I genuinely thought I could help the Liverpool Scene if I could catch a bit of that action. I’m being brutally honest here. I think Mike and Adrian thought I was being a bit stupid, and self-seeking. Anyway I did my best, but the whole LS in the US attempt had lost its wheels long before my half-assed attempts at rescue. Anyway the legacy of the whole experience was that we stopped being a close-knit, happy band, and Home Grown was a symptom of that. Sandy was covering the bases, I think. I was probably the most obvious person in the Scene to have the prospect of a musical life beyond the band, and he set out to promote that, and succeeded for a while. The most shameful thing for me was that I didn’t get on board the Made In USA sessions until we were already in the studio in January 1970. By that, I mean that I had no faith in that particular project, and contributed hardly anything to it in the preparation stage. It didn’t have a place for a pop star, and I was against it – until we started to record. Then it quickly dawned on me, first day in Sound Techniques, that it was going to be really remarkable, and I got down to it. Fortunately the end result was, for me, the single most important track of Liverpool Scene’s legacy, and I was able to contribute significantly – musically to some extent, but more tellingly on the technical side, working with Sandy on the collage, FX-laden side, and compiling the snippets, engineering on crossfades, etc. I have always had a technical brain, and I loved the creative possibilities of the studio, which chimed well with Sandy beginning to emerge as a competent producer – we learnt together. I don’t think the others had the same understanding of the studio process, except Percy, who is an electrical wizard, but he is so laid back – I got excited and went for it more. PT: Who were your influences? I hear a little Jansch, perhaps Nick Drake, as well as a little Al Stewart and, perhaps, Keith Christmas, who were also backed by Mighty Baby on his debut LP around the same time? AR: Gosh, this is all wrong, really! First, to deal with your suggestions. I saw Bert Jansch with John Renbourn, when I was at University, probably 1967. I preferred John – he had a better tone and a better technique. Of course, Bert was the writer, but I was always into guitarists rather than songwriters. So definitely not Bert! Nick Drake didn’t do anything for me, probably for that reason. I didn’t even start to listen to him until 1973, when Grimms were signed to Island, and I happily went home with 35 albums from the stock room. Then I began to hear and appreciate the class, but he was not an influence, ever. I did get to know him slightly that year, though by then he was pretty withdrawn. I particularly remember running into him in the street, while I was waiting to meet Viv Stanshall for lunch at a Greek restaurant called Anemos in Charlotte Street in London. Viv never showed, and Nick came with me to the restaurant. He didn’t eat, and he didn’t speak much, just sat there in his long tweedy overcoat, in the full sun of the midsummer of ’73, or maybe it was ’74. But he was calm and I didn’t form the impression that he was unhappy or depressed or anything, just preoccupied. It was a shock when he died, as I didn’t know him well enough to be aware he was sick. And I never anticipated the influence he has been on so many people since, though I can see why, of course. Al Stewart. No! I hated his Bedsitter Images phase. I thought it was mawkish, and adolescent. I got to know him in the 70s, because he hired such great players, Tim Renwick and the like, who were friends of mine. Then I just liked to hang out with his band. And I get on well with him when I see him now, though that is very infrequently. But actually, musically, I don’t get it. He has a couple of nice songs, but the punters turn up in large numbers, even now. He still does big spaces on tour, and fills them. Beats me, but I’m obviously in the minority. And I don’t understand why he is so camp onstage! Never did. Now, my actual influences. It’s hard to narrow them down, as I was an avid consumer from an early age, and I had a catholic approach – I was as crazy for the classics as I was for pop, skiffle, and later, rock and blues. The most influential? Big Bill Broonzy, Flanders and Swann, Jeff Beck, Bo Diddley, ‘Spider’ John Koerner, Steve Miller, and by 1970, above all others, Roy Harper. I had seen Roy early on at Les Cousins when he was frankly a bit rough, but I was blown away by Folkjokeopus and I got to know him well on the circuit around the time of that album. Adrian hated him as he always overran his set time, making us go on late and stuff. But I thought he was just great. Anarchic and musically inspiring. I used to stay at his place in Kilburn when I came down to London, in the same room as that fucking monkey! PT: Where did you meet up with Mighty Baby? AR: As I said above, Sandy suggested we use them on the Home Grown sessions, and I certainly had no alternatives to offer up. They were great to work with. Ace (the bass player) was a bit slow on the uptake (or stoned!), but he was a solid rhythm section with Roger Powell, and together they had a groove a mile wide. Ian Whiteman was certainly eccentric, but he could play anything brilliantly – one of the most extraordinarily gifted musicians I have ever met. And a major contributor to Liverpool Scene’s Made In USA only a couple of months later. PT: ‘Just For The Record’ and ‘Applecross’ have a bit of a raga feel to them. Did you ever consider exploring that direction further? AR: I don’t recognize much Indian style in those tracks – well, a bit in Just For The Record. But there is a huge debt to Indian music in Liverpool Scene’s Love Story and Come Into The Perfumed Garden Maud. In 1963 I went to the Edinburgh Festival for the first time, as a violinist, to play in an orchestra called the Edinburgh Rehearsal Orchestra. I was only just 17. I saw that, as part of that year’s Festival, Yehudi Menuhin was giving a free lunchtime concert in St John’s church at the corner of Princes Street and Lothian Road. Naturally I went along. Yehudi played a short solo recital to open the proceedings, and then explained that his true intention was to give a platform to two fellow musicians whom he greatly admired. These two friends of his were Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. So I heard arguably the world’s greatest sitar player, and the world’s greatest sarod player, introduced by one of the world’s greatest violin players, for free, one lunchtime. I thought the sound of those instruments was spell-binding – I could have listened for ever. When I got home from the Festival I bought albums by them both. Then for the first time I heard the sound of tablas (at the Edinburgh concert they had only been accompanied by the tambura). I devoured anything I could find on the history and theory of ragas and talas. I gave an illustrated lecture at my school, called Indian Music of Strings and Drums. I was obsessed. My brother is nearly 5 years older than me. He is a doctor, and at that time in 1963 he was studying at Guy’s Hospital in London. Because of my ability (and compulsion!) to perform he asked me to go and stay at the Hospital over that Christmas 1963, to help in various ways. Obviously, hospitals have to be staffed over the holiday, and, when the doctors and nurses finished their shifts, they would traditionally put on an entertainment for themselves, which was called the ‘Residents Play’. This was a pretty impromptu affair, full of medical in-jokes, but I was useful, as I could sing and play, and loved to occupy any stage. During the daytime, I would go round the wards, singing carols, and generally entertaining the patients, particularly the children in their own wards, Caleb and Diplock. Then I was asked to go and entertain at another hospital, St Mark's Hospital for Fistula and other Diseases of the Rectum (I kid you not!), with a similar purpose – to provide seasonal entertainment for patients. While I was being shepherded around St Mark’s I was asked if I would go to see a patient in a side room. There I met with an Indian lady, I would guess in late middle age. Her name was Princess Sharda Raje of Baroda, she told me. I sang a bit, and then we talked. I started to go on about my obsession with Indian music. Sharda told me about her daughter Ujwale, who was studying in London, and asked if I could chaperone her around London while she was there. The personal bit doesn’t matter, but the result of this encounter is that, in 1964, I was offered a free place at Baroda University, to study Indian Classical Music. I shall go to my grave with part of me regretting that I was too narrow-minded, or scared, to accept the major change this would have made in my life. I could expand on this for hours! But you touched on a very old and very deep part of my musical psyche with that question, as you can see. The sole legacy of it all are those hints of raga in that early work – I never touch on it now, as far as I am aware. PT: Were you influenced by that eastern style that Martin Stone had started exploring on the second Mighty Baby LP, Jug of Love? AR: No. I think I only met Martin once in my life – he didn’t play on any of my tracks. However, I was impressed by Mike Bloomfield’s work on the Butterfield Blues Band’s track, East-West. PT: What were you listening to when you composed the tracks on your debut? AR: Sandy and Jeanie Darlington, Spider John Koerner, Pete Seeger, John Fahey, Son House, Jimmy Guiffre, and Sleepy John Estes. PT: Your fans are legion and extremely loyal, and with all the “famous” musicians you’ve worked with during your career, we’re frustrated that you’re not the household name you deserve to be. Do you think your labels were partially to blame – not being sure how to promote your music: singer-songwriter, pub rocker, folkie? AR: No, I really don’t. Apart from a brief moment of confidence in 1973, at the time of recording Andy Roberts and the Great Stampede, I was at best ambivalent about having a solo career, as opposed to being part of a band, or a creative team of some kind. Deep down I’m very shy – I just learnt to disguise it. However, I love being onstage, and performing. It’s just that my true comfort zone is being one step to the left of the guy in the spotlight, rather than actually being in the spotlight myself. I went along with Sandy’s notion that I should be a solo artist, and I loved making the records, but in truth I was a poor prospect for any record company as I would always drop out of a solo career to form a band. For instance, I did a major tour supporting Steeleye Span, to promote my second album Nina and the Dream Tree, the gigs went really well, but I went straight into the formation of Plainsong after the tour. Of course, Sandy was very happy about that, as he produced us. But I was happiest standing in the giant shadow of Adrian Henri. PT: The album’s had a long and winding history, reissued on another label with songs dropped and added and even combined with tracks from your second album for its US release. Was it your decision to remix it and were you involved in the process or was it all done by the new label? AR: Home Grown got swept along by Sandy Roberton’s ambitions for his company, September Productions. When we first met he was working for Chappells as a publisher, but by 1970 he was in an expansionist phase, and he formed a relationship with B & C Records (it stands for Beat and Commercial)! He ended his deal with RCA, leaving them with a sell-off on the product they already had, and proceeded to release all his stable of artists on B & C, and their subsidiary label, Pegasus. After the Liverpool Scene split in May 1970, Sandy did a deal with RCA to let us retain Home Grown. We had released the Everyone album in the autumn of 1970, but after the crash which killed Paul Scard the future was very uncertain. I was keen not to go back on the road, and fortunately I got offered the job of working with Iain Matthews on his first solo album, which led to months of session work. Sandy decided to re-release Home Grown on B & C to buy me some time to get myself together, as I was still in a bad place, understandably. I took the decision to ditch some tracks which I felt weren’t up to snuff, and to re-record aspects of things which I felt could be improved. Some of those changes were mistakes, I now think, but at the time that was what I decided to do. So, for instance, we replaced the lead vocal on Moths And Lizards In Detroit. I thought it was better, but when I compiled the Sanctuary collection in 2005, I found I far preferred the original – more soul and honesty, less mannered and considered. But some things were improved in the remix, I think. It’s quite interesting to put the tracks up against each other and to hear the differences. PT: Were all the songs composed at the same time, or did you compose songs especially for the reissued edition? AR: All my vinyl is in storage at the moment, so I can’t remember what was on which album! My instinct tells me that the new stuff was written more recently than the original versions, so, yes, the new stuff was contemporary with the new release. Make sense? PT: Which version do you prefer – the original RCA release or the later remixed versions? AR: A bit of each, I think. PT: Several of your lyrics reference the geography of the states (Chicago, Detroit, NY, NJ) and the album has a US vibe in parts. Were Mighty Baby involved in any of the arrangements or did you do them all yourself? I’m particularly thinking of tracks like ‘Creepy John,’ with its rolling, country rock, Grateful Dead vibe and I know they heavily influenced Mighty Baby. ‘Jello’ has an Arlo Guthrie air about it and even the ‘Gig Song’ reminds me of early New Riders. You had toured the US – were you overwhelmed by the expansiveness of America and did that influence any of your songs from this period? AR: Well, songs like Home Grown and Moths And Lizards were written on the Liverpool Scene’s US tour, and were a direct result of it. I have always leant towards American styles in music. My generation did, I think. The arrangements were head arrangements, evolved in the studio at the time of recording, and the guys from Mighty Baby gave masses of input, definitely. It would have been an entirely different album without them, particularly Ian Whiteman’s amazing skill – check the Mellotron on Queen Of The Moonlight World, or the electric harpsichord on Moths And Lizards, and the swirly organ on Applecross. PT: There are a couple of songs with religious overtones – ‘John The Revelator,’ ‘Where The Soul of Man Never Dies.’ Were you going through a spiritual rediscovery, perhaps brought on by the tragic death of Paul, your roadie? AR: No. Nice try! But I sincerely like gospel music. The Son House album Death Letter was big with me in 1969. The gospel stuff carried on with Plainsong, who did I’ll Fly Away and Turn Your Radio On. When I got married for the first time in 1973, I asked Richard and Linda Thompson to sing Life’s Railroad To Heaven as one of the hymns in church. I have Tom Newman’s recording of the service somewhere in storage. PT: By the way, have you since titled that ‘Untitled Piece’? AR: No. I never even played it after the Liverpool Scene split. Like Graham Parker, there were times that it seemed like each new album saw a release on a new label. Was it frustrating bouncing from label to label, having to get used to a whole new set of promoters, A&R men, etc? Did you feel like you had to prove yourself to the “suits” with each new album? PT: There are a couple of retrospectives out there (Best of, Mooncrest, 1992; and the double CD Just For The Record… Solo Anthology 1969-76, Castle/Sanctuary 2006). Were you involved in the track selection and do you think these compilations are a fair introduction for newcomers? AR: I had nothing to do with the Mooncrest one, though I didn’t mind the attempt to cash in on the old tracks. It’s all profile building, was my thinking. The Castle collection involved me in months of work, but it was well funded, and I realised that, since it would happen with me or without me, it made sense to be on the inside. I was very happy with the result, and it led to the then Castle MD, John Reed, being the instigator and prime motivator for the Liverpool Scene 2-CD retrospective [The Amazing Adventures of (Esoteric, 2009)]. PT: Are you working to try to get the original albums reissued in their entirety, perhaps with bonus tracks? AR: No. I prefer the compilation approach, with new notes, and a contemporary assessment of the quality of the tracks. I respect the fact that people want to replace albums they loved years ago, but in my case there aren’t really enough of those kind of people to justify it, it seems to me. Actually both Home Grown and Nina And The Dream Tree were released quite legally in Japan only a couple of years ago [in 2007], as facsimile editions, on Strange Days. They did The Great Stampede as well. But no bonus tracks! And some maggot-brained cunt bootlegged Urban Cowboy. PT: You’ve always seemed to have some of Britain’s best musicians assisting on your solo LPs, from Mighty Baby on the debut to Zoot Money, Ray Warleigh, Gerry Conway, Ollie Halsall, and of course Iain Matthews. Was it difficult working with a revolving door of musicians as opposed to the constant interplay of the band setting you had within Liverpool Scene or Plainsong or Grimms? AR: Absolutely not! It’s always been my privilege to call on the cream of the UK’s session musicians to enjoy good times with. Those people bring so much to a track. I hired Crazy Horse for a movie session (Mad Love) I did in 1995, in the Capitol tower in Hollywood. You get an amazing lift from having people of that calibre around. The only trouble with the Horse was that Disney recut the movie after the recording, so the one really substantial piece we recorded didn’t get used. I have it, of course, but I can’t release it, as it’s owned by Disney, and the deal with Crazy Horse was for film use only. Maybe one day. That film had incredible stuff in the score. The end song was written by Billy Bragg, sung by Kirsty MacColl, with Richard Thompson on lead guitar, John Pattitucci on bass, and Jim Keltner on drums. Now that’s a line-up! And they never released the movie version of that song on CD either, just a wimpy acoustic version, because they (Hollywood Records) thought it was too grungey! Idiots PT: Putting the shoe on the other foot, you’ve been invited to contribute to albums by the cream of British royalty: Richard Thompson, Roy Harper, The Bonzos, and a trio of lovely lasses, Bridget St. John, Maddy Prior, and Shelagh McDonald, among many others. Which do you prefer, having guests on your own albums or being the hired gun (without all the responsibility of pulling off an entire album?) AR: They’re two different things. It’s flattering to be asked to contribute to someone else’s record, for sure, but it’s much more serious to pick players who will make your own material come alive. But most of the sessions I did for other people were at a time when they weren’t as legendary as they may appear today, looking back. For instance I played on Richard’s first solo album in 1971. Hell, that’s 38 years ago! I hardly ever even see him now. My biggest thrill, probably, was being asked to join Roy Harper in 1975, which led to us working together for 5 years. He’s an acquired taste, but I learnt so much from him – not technical stuff, because he only plays his way, but the breadth of his musical vision in the early 70s was staggering. I heard Stormcock played back in Abbey Road Studio 3 the day they did the final mix and cut it all together. Roy, Pete Jenner and I with a big spliff: it could never be better than that. Of course Roy is a mate, who I’ve known for over 40 years, but the Nina album couldn’t have been made without hearing Stormcock, which led me to experiment with symphonic, episodic songs. PT: With the second album, did you make a conscious effort to write more accessible tracks – or did the label have any suggestions about the tone of the album? ‘Good Time Charlie’ seems like an attempt at a hit single, or at least some radio airplay? AR: As I said above, I had no relationship with B & C, only with Sandy. The songs are mostly about my then relationship with the actress Polly James. She helped me get through Paul’s death, and she had troubles of her own. It was never going to last, but Keep My Children Warm, 25 Hours A Day/Breakdown/Welcome Home and particularly I’ve Seen The Movie are all about Polly. Actually, looking back, I think that Good Time Charlie sticks out as being in a different style to the rest, and it would probably have been a better album if I’d omitted that track, which is the only one I didn’t write, and was a hangover from the Everyone days. PT: I’ve noticed that ‘I’ve Seen The Movie’ was compiled on the Fading Yellow series. Were you consulted on that and had you noticed any renewed interest in your material after the series came out? AR: I don’t know anything about this. Tell me more. I don’t own it, so it would have been done without my involvement. That sort of thing stinks, don’t you think? Your work gets traded like fish fingers, and you never get a copy, let alone any money. I’ve been bootlegged, too. PT: A couple of years later, Elton released Goodbye Yellow Brick Road with a track called ‘I’ve Seen That Movie Too.’ Did he ever contact you about whether he was influenced by your song to compose his “answer song,’ or do you think it’s just a coincidence? AR: If he feels the same way about my music that I do about his I’d say “coincidence”, wouldn’t you? PT: The epic title track, ‘Dream Tree Sequence’ has several sequences that seem improvised in the studio. Had you given the musicians any guidelines on where you wanted the track to go, or were they free to improvise around you? AR: It was recorded in several sections, and I worked with Zoot in the studio on the transition into the final section. Now that man is a genius, and I’ve been very, very lucky to be able to call on him as a piano player. But there isn’t much actual improvisation – it was pretty well arranged ahead of the session. Yes, we toured it in support of Steeleye Span in 1971. The first performance was when I was supporting Procol Harum at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and I hired Ian Whiteman and Roger Powell for that, with David Richards on bass. Later, David joined Sandy Denny’s band, so I lost him, and the Steeleye dates were played by just me with Bobby Ronga on bass, who I brought over from the US for the purpose. Then Iain Matthews came to a show, and the Plainsong idea was born…… And yes, we did the Dream Tree Sequence right through that time – it wasn’t hard to play live. I still really rate the Nina album (apart from Good Time Charlie)! PT: You did a few gigs as the “surrogate” Pink Floyd during their German and Earl’s Court performances of The Wall. Did it get frustrating performing the same show night after night or were there opportunities to stretch out and jam with David? AR: I didn’t do it for long enough to get bored. I was extremely flattered to be asked, and the whole gig was only 13 dates – 8 in Germany, and 5 at Earl’s Court. It was a great experience. Big stadium shows, well paid, a better class of drugs, and large scale theatre to die for. There was room to jam in the show – there were bits designed to let the wall builders catch up, for instance. Even in the formal bits it was different every night. Every note was played live, apart from the school kids’ voices on Another Brick, and the Michael Kamen orchestral arrangements for the trial, and even that had a live vocal. It was a fantastic gig for me, and I was very chuffed to be on the live album of the show, 20 years after being in the band. PT: You’ve recorded a few soundtracks – is the writing and preparation process different that writing a more traditional solo album? Which do you prefer? AR: God, yes! In film, the sole reason for the music is to serve the film. You work in consultation with the director, who ultimately carries the can for it all, the producer(s) who are paying, the sound and music editors who are responsible for the quality, the final mixer who compiles the final track. It’s the biggest collaborative process you can imagine, and I adore it. I’d drop everything to do a movie. The best times were when I was scoring, for sure; no record comes close to that level of satisfaction. And that’s not to mention the glamour, the Oscar parties, painting your toenails by the pool…. PT: The Grimms project seemed to combine the best of the Bonzos’ approach and set the stage for Innes’ future work with The Rutles. You’ve enjoyed the theatricality of the material here and in your future work on The Wall gigs. Do you have fond memories of these recordings and, if you had to pick one, what would be your favourite project from your post-LS bands and why? AR: I doubt Neil would see Grimms as a stage-setter! You’re right – I do love theatre. There have been many, many highlights since the Liverpool Scene. The theatre writing days, which led to TV, and music directing at the Royal Court, the Floyd of course, the Hank Wangford Band, Roy, the movies, silly stuff like Rolf Harris at Glastonbury 1993, Plainsong all through, countless poetry gigs, producing Willy Russell, the Dennis Locorriere tour of Dr Hook hits, it goes on and on…. Pick ONE? Can’t do it. PT: You appeared on dozens of albums throughout the 70s, but no real solo efforts over the past 35 years. What’s kept you away from recording your solo stuff – have you just stopped writing material? AR: I haven’t stopped writing, but I don’t write many songs. There was a situation, which arose in 1973 surrounding the release of the Great Stampede album, which led to my turning to theatre as a means of expression, and consciously turning my back on a recording career. It was my salvation. If I’d stayed trying to be a solo artist with a record contract, I’d have been finished by 1980. Theatre led to TV, which led to film, which led to the only sustained decent income I achieved in my career. So it was definitely the correct choice, and it has made me what I am. I am extremely lucky to have had modest success in so many different fields, and I wouldn’t change any of it. Well, I might have been a bit more smarmy when it was Danny Boyle’s job to make the tea in 1979! PT: You recently did a few gigs with Three Bonzos and a Piano? Just like old times, a la Grimms? AR: The gigs have been a lot of fun. However there is a fundamental difference between the two. With Grimms, the music was serious, and we worked hard to perfect whatever it was we were doing. With the 3 Bonzos, it ruins the show if the music is in any way slick. It’s hard to explain, but it only works if it appears to be a shambles! So, it’s a totally different approach. And the 3 Bonzos don’t perform any Neil Innes material at all. PT: What can your fans expect next? AR: I’m currently working on the formation of an acoustic guitar trio with Mark Griffiths and Clive Gregson. We can’t do too much right now, as Griff is out on tour as the bass player with Cliff and the Shads, and Clive still lives in Houston. We’re targeting early 2011. But the early signs are that it is a very interesting and different grouping, for which we have high hopes. And in January I’m teaming up with Hank Wangford again, to do some gigs as a duo [“No Hall 2 Small”]. Brad Breath – high in the saddle again! Written by Jeff Penczak, edited and directed by Phil McMullen © Terrascope Online December 2010 |

|---|