We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

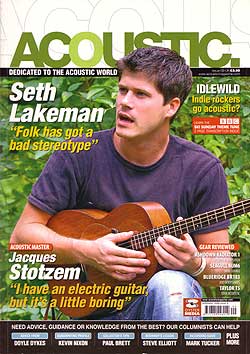

The Ptolemaic Terrascope magazine gave the site permission to use this interview years ago when this website was first set up.... Many Thanks.

BIOGRAPHY

The Ptolemaic Terrascope

PT: Let's start at the beginning.

AR: I was born in North London, a place called Hatchend and I lived there until I went to University in Liverpool in 1965.

PT: Were you playing by then?

AR: Yeah. I was always musical. I was lucky because my parents really wanted to involve me in things. My dad was nuts about The Crazy Gang and I remember being taken to see three Crazy Gang shows at the Victoria Palace - it was like the end of Music Hall, really. And my Mum took me to symphony concerts. When I was nine I decided that I wanted to play violin, so they fixed it for me to have violin lessons. I stuck with the violin until I was eighteen.

I got a plastic ukelele for Christmas one year - 19/11s it was, I wish to hell I'd kept it. That was around 1957, the skiffle era and I was into Lonnie Donegan and Johnny Duncan and listening to Radio Luxembourg. I got a music scholarship to a public school in Essex - when I went there, there was already a band called Flash Sid Fanshawe and the Icebergs. This was in 1959, they'd got guitars which they'd made in the school workshops and played very simple stuff which I thought sounded fantastic. I used to go and listen to them rehearsing and just hang around because I was extremely junior, and they all had quiffs and looked fantastic (laughs). By the time I left the school there was half a dozen quite good bands there, we'd rehearse on Saturdays and Sundays. You could plug in and just make as much racket as you wanted.

PT: So what was your band called at school?

AR: We ended up as Monarch T. Bisk. Originally it was Monarch T. Bisk and The Cherry Pinwheel Shortcakes but nobody could remember it all. By then we were attempting to have long hair and not get caught and were playing real R&B - Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters, that kind of stuff. We went though several stages - at one time we were The Sinners, that was our Shadows period. But I never thought of doing it for a living. I guess I got my first guitar in 1959 or '60 - a Spanish guitar, which I've still got.

1964

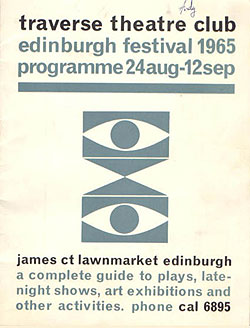

It was a series of total accidents which led me to going to Liverpool and being thrust into a performance situation. I went to the Edinburgh Festival in 1963 and '64 playing violin with a rehearsal orchestra. One night in '64 I went out and found this place called the Traverse Theatre Club where there was a late-night folk show - it was Owen Hand and Hamish Imlach, the first time I'd ever seen anything like that and I thought it was fantastic.

A bit later on that year I ran into a guy at a party who was the older brother of the drummer in the band I'd had at school, a chap called Max Stafford-Clark. Max said he was going to Edinburgh to do a play and would I write a tune for it? I was eighteen and kind of drunk or stoned or something and I didn't take it seriously. Then he phoned up and asked where it was and of course I hadn't done anything. So I got his brother John, the drummer, in and wrote this little guitar thing - just electric guitar and drums. Recorded it on a Grundig at home and sent it to Max. He liked it, used it, and phoned me up a couple of weeks later to say this guy who was going to play guitar for a late-night review they were doing couldn't make it and could I come up and write and play the music? I took an electric guitar and an amplifier and John took his drum kit and we went up and played this review, which happened to be at the Traverse Theatre Club. We played for a fortnight, about an hour each night, and after us was Lindsay Kemp with Jack Burkett, The Great Orlando, plus this young student of his called Vivian Stanshall, doing mime and playing the tuba and generally camping around. I was sharing a dressing room with Viv, the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band had just started and he told me all about that.

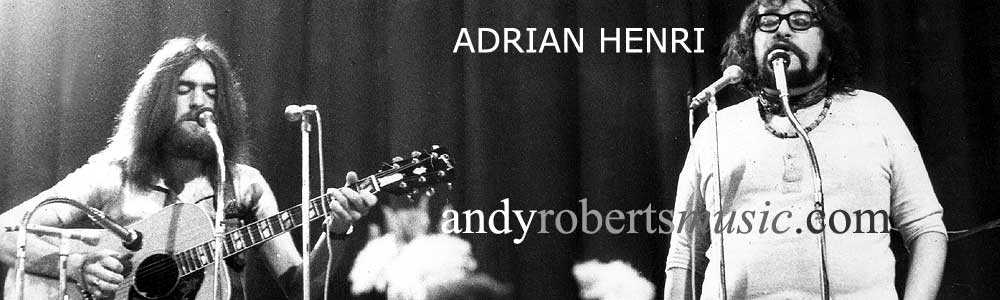

Following us in for the third week of the Festival was this funny theatre team from Liverpool called The Scaffold. Didn't know anything about them. Somebody said oh yes, Paul McCartney's brother' - ooh! Really impressed, you know. I went to see their show and thought it was wonderful and that's how I met Roger McGough, John Gorman and Mike. With them was all these other people like Pete Brown, Spike Hawkins, Brian Patten, Adrian Henri, all these poets - they were doing a poetry show at The Traverse in the afternoon. All these people who have remained friends and collaborators were all focused on this one little theatre.

After I got back to London I accepted a place at Liverpool University and the day I got there I bumped into Roger McGough in a bookshop in Renshaw Street. He later suggested some poetry and music collaborative stuff and February 1966 was the first time I did a thing with him and Adrian Henri, at The Bluecoat Theatre in Liverpool. It just took off from there. Within a couple of months I was doing poetry events at The Cavern and playing with a band at the University. It was a town where there was loads going on and was very much the community serving itself - two and six to get in, and everybody got together.

Of course, the Merseybeat thing would be on its way out by then? The people that were left were the also-rans and wannabees. There were bands that missed the boat. We think of Liverpool in terms of Gerry & The Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer and obviously The Beatles. That was the public image of it. But the people who lived in Liverpool had a different perspective on it entirely. They were into bands like The Roadrunners and The Clayton Squares. The scene was moving towards soul and R&B. Faron's Flamingos, that was the other band that people said were really the best band - much better than The Beatles had ever been. But, of course, they never did anything. I mean, Bill Faron is still playing up there now.

1967

PT: You were in The Clayton Squares, weren't you?

AR: No, that's a myth. It's because it was in this book (Encyclopedia of British Beat Groups & Solo Artists of the Sixties, compiled by Colin Cross with Paul Kendall & Mick Farren, Omnibus Press, 1980). Mike Evans was the sax player with The Clayton Squares, that was the tie-up with The Liverpool Scene. Mike Hart (also of The Liverpool Scene) was working under the name of Henry Hart with The Roadrunners. There was a really lively club scene. I wasn't really part of that though, I was part of the poetry and latterly the theatre thing. I did a lot of stuff, largely unpaid, for the Everyman Theatre.

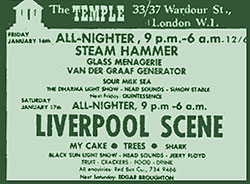

We started getting things like a spot on the BBC2 arts programme 'Look At The Week' - 5th March 1967, so it was a bit before the Summer of Love. Roger, me and Adrian went with The Almost Blues. Joe Boyd asked us to play the U.F.O. - we did a Liverpool Love night, when it was at The Blarney Club in Tottenham Court Road. London seemed a long way away and what was happening there didn't really affect us. We had our weekly gigs at O'Connors Tavern which was just individuals coming together doing shows. We started getting booked as The Liverpool Scene Poets - it was the book (The Liverpool Scene, Rapp & Carroll 1967) that really focused that. And also the Penguin Modern Poets No. 10 (Adrian Henri, Roger McGough, Brian Patten) came out within a year of that. Initially it was Adrian and Roger particularly, they were really into the performance thing - Brian was a bit stoned out in those days and very much into being the lyric poet. Mike Evans also wrote poetry and played saxophone, Mike Hart wrote songs and played guitar, I wrote songs and did accompaniments for poetry. So the five of us would go out as The Liverpool Scene Poets and get booked at local Domestic Science colleges. Nothing further afield than Warrington really, all local stuff. I was working with The Scaffold as well by then, as a back-up musician. And then The Scaffs started having their hits. 'Goodbat Nightman'... That didn't make it. '2Days Monday' was the first one that got a sniff, then 'Goodbat' didn't happen, then 'Thank U Very Much' really became huge, and then 'Lily The Pink' which came out of a show I'd worked on. I was there the day Roger said I've got these words, it's an old rugger song we used to do......

We thrashed it out in John Gorman's flat, I also played on the record. So that was moving, which meant Roger couldn't do the poetry thing. At that time I suggested to Adrian that all we had to do was add a drummer and bass player and we'd be a band. So I got Percy Jones, who later on was with Brand X and now lives in America and has become a sizeable jazz player - he was the bass player in The Trip, which was my university band. And we found Bryan Dodson (drums) who was playing cabaret at the Wookey Hole or somewhere, and went out and did the first gigs like that. And that was The Liverpool Scene band from the first show.

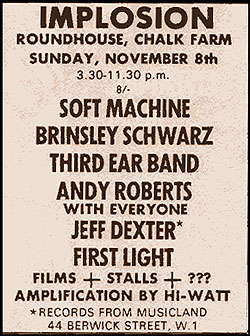

Then we met John Peel. I used to listen to his radio programme 'The Perfumed Garden' when I came down to London. He played a track off 'The Incredible New Liverpool Scene' which was the very first album (prior to the band forming) on CBS. That album was recorded in two hours one night after a gig at the ICA at Regent Sound in Denmark Street - in mono. It was going to be Roger, Adrian and Brian - Pete Brown couldn't make it. Then Brian ducked out on the night, got pissed and didn't want to do it. It ended up just Roger, Adrian and me. I went up to The Roundhouse for an Implosion or something and Peel was there, so I said Hi - I'm Andy Roberts, thanks for playing the record and so-on. He started visiting us in Liverpool, he loved the scene up there and then he started getting us booked on shows. People would come and ask him to come and talk and play some records because of his clout on the radio, very much an underground thing. He'd do it for nothing but expenses, but he would want them to book two of certain acts. Like Tyrannosaurus Rex, Davey Graham, Roy Harper, Liverpool Scene, Principal Edwards - things he was very much into at the time.

Then Sandy Roberton wanted us to do an album and Peel nominally produced it - he sat there and listened while we made it, basically. That was the first album ('Amazing Adventures Of', RCA 1968). I graduated from University in 1968 and immediately turned professional and went on the road with Liverpool Scene, having already had quite a big taste of showbiz with The Scaffold. But I ducked out of that after 'Lily The Pink' 'cause it was all so big. They were working every night and I was a student, I couldn't do it. In 1967 though we did that 'McGough & McGear' album. That's the one with Hendrix on it. Oh, everybody, yeah. John Mayall, Graham Nash, and of course Paul McCartney produced it and played on it. It was just everybody who was around really. Done in a couple of nights at De Lane Lea when it was in Kingsway. I was not professional at the time, but I was doing jobs that many professionals would have envied. I'd get calls to do a bit of recording in London, and I'd just get into the back of Mike's car and go down and stay at Paul McCartney's house. I'd go off and do stuff and come back by tube and walk up and ring the doorbell, and there'd be eighty-five girls hanging around outside. You'd go into this house which had the 'Sergeant Pepper' drumskin hanging on the living room wall, and Paul'd be playing you his stuff. I didn't even think about it twice. 1968 was really when the working life started.

1969

PT: The Liverpool Scene was still together when you did your first solo album, 'Home Grown' in 1969?

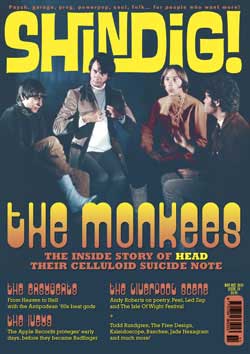

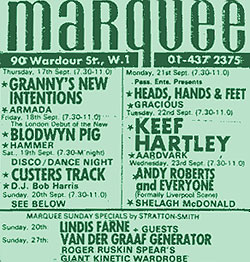

AR: That's right, 1969 was a great year because we got on the first Led Zeppelin tour - Blodwyn Pig, Liverpool Scene and Led Zeppelin. We played The Albert Hall, we played the Bath Festival of Blues which was great, there were twelve really great acts on. We ended up, July of that year, at the Isle Of Wight Festival, playing on the same day as Bob Dylan and The Band to 150,000 people. About a week after that we flew to America for a three month tour. Disaster - absolute disaster. That was when we suddenly came up against the utter reality of it. What we could make work with a British audience, given this poetry and a band that were never rehearsed, we got away with it through being so different and our verve and irreverence - the fact that we would take the piss out of things. None of which worked in America. Our first show there was playing to 17,000 people supporting Sly and the Family Stone at Kent State University, in a sort of aircraft hanger. We were still using 30 watt amps, Sly had got in thousand watts for everything. We came up against a very stark reality. So, although we slugged through the tour and played a lot of interesting places, there were nice shows that I remember with great affection, it really caused the whole thing to be re-appraised. We played at the Midtown Theatre in Detroit, the bill was Joe Cocker & The Grease Band headlining, The Kinks were second, Grand Funk Railroad were third, Liverpool Scene were fourth and bottom of the bill was The James Gang with Joe Walsh on guitar. I had to follow Joe Walsh in 1969! Unbelievable. I was stupid enough to still think I could be Jimi Hendrix. I wanted to be a star. You do when you're young - you don't realise that everybody has their role, and that wasn't mine.

PT: You'd had some personnel changes by then, hadn't you?

AR: Yes, we lost our drummer. Bryan got TB. It was half-way through the Led Zeppelin tour. We had no idea he was desperately ill, we thought he was just being a drag. He was within days of dying when we got this panic 'phone call from his girlfriend, Jackie, to say he had tuberculosis and that we all had to go to hospital to be tested - none of us had it though. We had a gig that night in Southampton as well. So we phoned up this guy called Pete Clarke who had been the drummer with The Escorts and asked him to help us out, which he did. The rehearsal for the Southampton gig consisted of me telling him in the van how the numbers went! He was a great drummer though and actually it was better than it had been with Bryan, because Bryan had been dying behind his kit for the previous two months. Clarkey became permanent after that. Bryan recovered eventually - he's still around, in Liverpool. The Liverpool Scene put out quite a few albums. Only three while we were still together. 'Bread On The Night' was recorded before we went to America, and when we came back we did 'St. Adrian Co., Broadway & Third' - one side of which was live, and it was ghastly, horrible. The other side was the first of the things I'm proud of though, although I had very little to do with it and at the time had resisted the band going in that direction. I thought it was too 'arty' - I wanted to take the band into the realms of rock & roll stardom. But looking back on it I can see that it's a bloody good job of work. That's the best legacy for what the Liverpool Scene was about, I think, we broke up, rather messily, on stage at the London School of Economics in May 1970 with Adrian attacking Mike Evans with a mike stand. Horrendous.

PT: It was that bad, was it?

AR: Terrible. There'd been a lot of tensions. By then we were onto our third drummer. Pete had left and we had a guy called Frank Garrett. He was only in the band for two or three weeks - nice lad, good player.

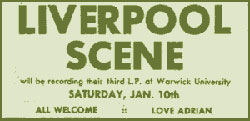

PT: What about the 'Heirloon' album?

AR: A lot of that was recorded for a show we did at the ICA about Guillaume Appollinaire called 'J' Emerveille' or 'I Wonder' with Tom Kempinski who later wrote 'Duet For One' and became a good playwright. He was in this just as an actor - he played Appollinaire. Other than that it was just out-takes from the live show at Warwick. We had nothing to do with it, it was like RCA's contractual obligation album. The band were gone by the time it came out.

PT: Your first solo album 'Home Grown' was also on RCA. Then it was re-released, re-mixed a bit and with different tracks on B&C Records.

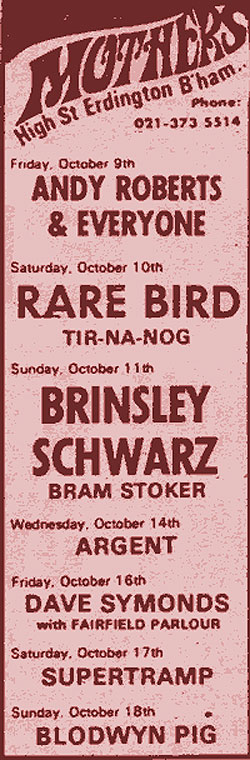

AR: I had this idea of putting a band of my own together. I stopped off at Kettering in Northants to see Principal Edwards who'd got a farm there. Stayed over a couple of days, got pissed with Les their lights man in the pub, came back and started racing motorbikes around the farmyard. And I came a terrible purler - ripped all up one elbow and was out of it for four months. About August we rehearsed the new band, Everyone. Unfortunately I was terribly naive. I could play, but I didn't know anything about bands. I thought all you needed was to get together a good bunch of people and the rest of it would happen. By then I'd met Dave Richards, bass player, who I got on terrifically well with. John Pearson was on drums. John Porter was a guy I'd met in Newcastle that I liked so I got him in as another guitarist. He recommended Bob Sergeant to play organ and sing. Which was probably the worst of several bad moves. Bob was a terrific singer, he came out of his own band Junco Partners and had a big bluesy voice and played very bluesy organ which wasn't at all what I needed. Anyway we put a band together and recorded an album which was frankly a bit schizoid, a bit of a mess because there was Bob's stuff and my stuff and it didn't really meet in the middle.

Then we had a horrendous experience... we'd driven back to London after a gig at Southampton University and were sitting in John Pearson's flat. We'd left one of our two roadies, Andy Rochford, in Southampton - he'd stayed there with a girl, and Paul the other roadie, had driven the van back to London. The phone rang and Andy and the girl wanted to come back to London and he asked Paul to go back and get them. So Paul drove down and picked them up, and on the way back, on the A33 at Basingstoke, they had the most horrendous accident. Paul was killed outright, Andy and the girl were badly hurt and the van, with all the equipment in it, was wrecked. So suddenly everything that kept the band on the road was smeared across the A33. Paul was nineteen and had roadied for me in the latter stages of the Liverpool Scene and had stuck through all my being smashed up in the Summer, so I felt very guilty. It wasn't my fault, but his loyalty had cost him his life. It's still a very difficult thing to think about. There were still some obligation gigs I had to do, which I did as an acoustic three-piece with Dave Richards and John Pearson playing tablas. Come December 1970 that was it, I didn't want to do anything.

1970

I was at home, living with my parents, and one day the 'phone rang - it was Paul Samwell Smith, who I didn't know although I knew who he was because he'd been the bass player with The Yardbirds. He was looking for a guitarist to work with an artist he'd just taken on... could I go round and see this guy, see if we could get on and help him sort out the songs - and that was Iain Matthews. This was for 'If You Saw Thro' My Eyes', it was the post-Southern Comfort Iain Matthews. Lovely album. So he was sussing me out, and I was sussing him out. We started getting on OK and that put me into seven months intense studio work with Iain and Cat Stevens and so-on. That was how I met all those guys like Dave Mattacks, Gerry Conway, Pat Donaldson. Then Sandy Roberton was saying I hadn't done a solo album for a year and should do something. I did 'Nina & The Dream Tree' which came out of a poetry tour I did with Adrian Henri in Norway in 1970. Largely to promote that I went out as a solo act at the end of 1971 with Dave Richards on bass and Bobby Ronga. In the meantime I'd been to America with Iain for two and a half months - with Iain and Richard Thompson as an acoustic three-piece in the Summer of '71. We were going to go as a band with Timi Donald playing drums and Dave Richards playing bass, but Iain decided he didn't want to do it that way. Bobby Ronga was our roadie. We co-opted him to play a bit of bass while we were over there, then I brought him to work with me on a tour I did with Steeleye Span at the end of 1971. I'd done a single show with Mighty Baby at the Queen Elizabeth Hall supporting Procol Harum - that went very well, and I was put on the Steeleye tour.

When I was on the tour Iain came backstage at one gig and suggested we became a band. So we got together in Iain's flat in Highgate and decided that if we could come up with a good version of 'Along Comes Mary', the Association song, we'd work on that. So we worked on it and recorded it at the end of the day and it came out really good so we decided yeah - let's do it. But we had to get Iain out of his management deal with Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley which cost money. We got the Elektra deal because Jac Holzman was into Iain, and that's how Plainsong started. It lasted the whole of 1972.

Also, in 1970 I'd worked with the Bonzo Dog Band for a while as the Bonzo Dog Freaks, which was only Viv Stanshall and Neil Innes by then as the others had left, with Ian Wallace and me. We had this idea of working together as Grimms, which was Gorman, Roberts, Innes, McGough, McGear, Stanshall. We actually did a couple of shows in 1970 - one at Greenwich Town Hall with Keith Moon on drums. While I was doing Plainsong in 1972 Grimms had finally gone on the road, initially with Mike Giles playing drums. Iain split at the end of 1972 and Plainsong finished before the second album.

PT: You actually recorded the second album though, didn't you?

AR: Yeah, it does exist, there's a finished version of it. And the demos leading up to it have just come out on a German CD.

PT: How did Plainsong finish - what happened?

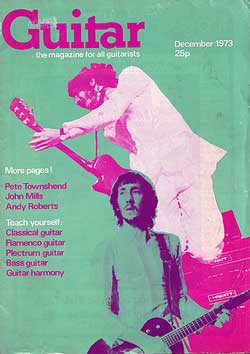

AR: There's a lot of background that I've only really come to know about since re-establishing a working relationship with Iain eighteen years later. It was all more to do with what was happening in his life than what was happening in the band. He was tempted away from the Plainsong situation by something that looked better at the time - to go to America and work with Mike Nesmith. Iain admits quite frankly that it was a mistake and that he shouldn't have done it, but that's part of life's rich pattern. There was tension between him and Dave Richards which was beginning to build up, and it got worse when the band split. I immediately went off and joined Grimms and got on with my solo things and put it all behind me. I did my first Grimms tour in March 1973, and it must have been soon after that 'Urban Cowboy' (the next solo album) came out, because one of the tracks was played by the Grimms band - 'Home At Last'. Then came the 'Great Stampede' album. At that point I thought I was going to be a solo artist, with Grimms on the side. I was really into it, psyched-up and ready, writing well. Everybody in the 'Great Stampede' band was willing to go on the road with me; Gerry Conway, Pat Donaldson, B.J. Cole, Mick Kaminski... I had a really hot band to go out. Then it all got screwed up. In 1973 Jac Holzman sold Elektra to David Geffen, which altered the distribution over here from Warner to EMI, and then the three-day-week hit. It had to be pressed by EMIs pressing plant at Hayes and they were overstretched due to only being able to press records three days a week and having to get their Beatles albums out in time for Christmas. So the thing never got a proper release - there wasn't enough copies, they weren't available on the declared day and the review copies didn't go out. It was heartbreaking.

PT: Following the demise of 'Great Stampede' you went into theatre work?

AR: I'd done some work as a student with Peter James who had been the artistic director of the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool. He offered me the chance to write the music for a musical, 'Mind Your Head' by Adrian Mitchell. It had been produced in Liverpool initially, but the problem was that ordinary actors couldn't sing the music, it was all too clever. They wanted something simpler and more direct for the London production. I had ten days over the Christmas of '73 to write it, then straight into rehearsal. The stage set was a 'bus, cut up and rebuilt. Through that I was asked to do my first television work, which was a thing called 'Something Down There Is Crying', a half-hour drama for BBC2 starring Elkie Brooks as a blues singer. By 1976 I was settling down to doing a bit of theatre, a bit of telly, the odd solo date. Then the next of the magical phone calls was from Roy Harper, who asked me to go out and play lead guitar in a band with him in America, which I did. And I got sacked after being there for a month or so, 'cause I got caught up in some desperate political situation with Chrysalis Records. I came back, Roy carried on for a couple or months or so and when he came back to England he apologised and suggested that we form a band, which became Black Sheep. I worked with him for five years, in bands and as a duo, which was pretty much the main thing I did until 1980.

Meanwhile, B.J. Cole, who was a mate from Plainsong days, said he was doing this album with Sam Hutt who worked under the name of Hank Wangford and invited me to play on it. Initially the money was put up by United Artists. We recorded four tracks and UA didn't like them, so they wouldn't put up any more money. So B.J. just begged everybody to finish the album anyway, which we did. Then he wanted to promote it - I said, listen, the last thing I wanted was to be involved in is country music... but he said it was only three dates to promote the album and the inevitable thing happened - I just took to it like a duck to water, I loved it. We had a hysterical time.

PT: Where does your stint with The Albion Band fit into all this?

AR: That was in 1979. I knew the Albions quite well because they'd played on the same bill as the Roy Harper band quite often. Ashley Hutchings wanted to put together more of a rock band, like the early Fairport - he wanted to feature Sandy Denny songs. He was going to get Julie Covington in to sing, but she got cried off at the last moment, I don't know why, so they got Melanie Harrold in. The band was Mattacks on drums, Ashley on bass, myself and Dougie Morter on guitars, Mel Harrold playing keyboards - we borrowed Dolly Collins' little organ - and Martin Simpson and Barry Dransfield. Terrific line-up, the music was superb. We did it in '79 and revived it in 1980 for about four dates. Mel later resurfaced with the Wangford band - the end of 1981 was when we really started putting that together. We'd done the early dates in 1980, but then we decided that we'd definitely make a go of it and be a band, which was the line-up that stayed constant until 1983. At one stage the whole band had to go off the road because B.J., drummer Howard Tibble, bass player Gary Taylor and myself with Ricky Cool went off to do a tour with Billy Connolly. He saw us at The Hope And Anchor one night and hired the whole band - apart from Hank and Mel, so it was a bit rotten for them, but he was offering us decent money to tour for a month, so we went off and did that.

1980

PT: I believe you also had a stint with Pink Floyd around that time.

AR: Dave Gilmour was a friend of Roy Harper and would occasionally show up, and it was always a great joy. I loved playing with him. He 'phoned me up in December 1980 and offered me a gig playing with Pink Floyd, so I left the Wangfords to their own devices for a period. Initially it was to play eight dates in Germany; then we came and played five dates at Earls Court after that because they wanted some concert footage for a film, which they ultimately never used.

PT: What was it like doing their music?

AR: Well basically you've just got to stand there and look good and get the notes right. There was still quite a lot of room for improvisation though. The whole first part of the show they had to build The Wall, so it would take longer some nights than others - there were pad areas built in where Dave and I would just jam until certain sections were completed, then it was time to move on to the next bit. It had to be organised so that the last brick went in on the last note of the first half. Because of my involvement with theatre it was interesting to see - it was a theatrical event. But any one person was easily replaceable. They had expanded to an eight piece, so they had a surrogate band... you got The Floyd, and then Pete Woods on bass, Willy Wilson on drums, Andy Bown playing keyboards and myself on guitar. At times the surrogate band would put on latex masks of the Floyd and go out and be the Floyd, just to confuse the audience. We would open the show for instance, you'd get the roar from 25,000 people and actually it was the four surrogates - the Floyd weren't on the stage. It was Roger Waters thumbing his nose at the crowd really - a bit sinister. We'd do the opening and the lights would go down on the front stage after the aircraft had crashed, then the lights would go on back stage and the same band would appear to be there, so people would think hang on - I've just seen them down there, what's going on?!?

1983

PT: You left the Hank Wangford band in 1983 - to do what?

AR: To do very little, in 1984 or 1985. I did my first feature movie - 'Loose Connections'. I did a touring play, 'Oi For England', about skinheads, it had previously been done for television which I had nothing to do with. I was also still doing little poetry gigs with Adrian. When the Wangford band broke up I had Bad Breath and his Two Buttes Band, just for a couple of dates.

PT; Why had the Wangford band broken up?

AR: It just wasn't going anywhere. It was totally co-operative when we first started, but it was obvious that that wasn't going to work, that the band had to feature Hank as a personality above the band, which of course was nonsense because Hank was a semi-pro, he was a doctor. The solid work was being done by the professionals behind him, but it was plainly not going to total up to anything... I mean, I couldn't devote my career to putting a semi-pro on the map, fun though it had been. I left a bit before everybody else, apart from Gary who had been replaced by a guy called Pete Dennis who worked under the name of Terry Lee Lewis. I loved the Wangfords, we had a terrific time. The Bad Breath thing was just for a couple of dates, then we decided we would carry on playing the London pubs for fun. I wasn't doing much else, they were pretty lean years. I had a band called The Tex Maniacs, which Mike Berry joined - it was good for him to do new music rather than old Sixties stuff. That folded, then we had a band called Irma And The Squirmers which was when Mel Harrold came back and started singing with us. They were great gigs, great fun but just only as a pub band. And then re-enter Paul Kriwaczek, who was by then a producer at the BBC doing adult education programmes. He was doing 'Welcome To My World', which featured Robert Powell as a sort of futuristic eminence grise, this man who wafted through the year 2020 and looked with a jaundiced eye back to the year 1985, seeing all the damage computers had done - the implications for international banking, for police surveillance, not being able to get your names off police files etc. Kriwaczek wanted me to use a computer to write all the music. Most of the programmes had about twenty minutes or so of music that I came up with through my use of computer and MIDI, and that started the ball rolling - I was asked to do music for Continuing Education all the time, then 'Thin Air', a five part drama serial. A producer who heard 'Thin Air' loved it and asked me to do an eight-parter for Central Television called 'Hard Cases' in 1988, and the TV ball started rolling really. Then in 1990 we were looking for something to do on a night out and in the Brighton Evening Argus we saw Iain Matthews was playing at a pub in Brighton....