We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

SHINDIG

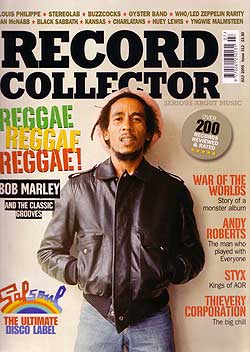

SHINDIG: A lot has been written about the material you recorded with Bob Sargeant that resulted in the album, Everyone. Confusion reigns supreme over that one, down to the title – is that the name of the album or the name of the band! Somehow it came across like two separate mini-albums – your half and his half. How do you feel about the record today? AR: The background to the formation of Everyone is worth exploring, as an indication of my state of mind at that time. Liverpool Scene broke up messily at a gig at the London School of Economics in May 1970. The band split between Mike Evans and Percy Jones on one side, and Adrian Henri and myself on the other. It was clear to me that my time in Liverpool was also at an end, so I returned up north to clear out my room at 64 Canning Street and I headed to London, to stay with my parents, at first. On my way south I went first to Leeds to spend a night with a gorgeous girlfriend there, and then on to the Kettering area to drop in on Principal Edwards Magic Theatre. They were old friends from the touring circuit, and at that time they were renting a large property called something like Broughton Grange Farm, and living as a commune. I went drinking with Les their lights guy that lunchtime, and returned to the farm half-cut, and started messing around with a motor bike they had there. I totally lost it on some gravel, went down to my left and ripped my left arm open to the bone, at the elbow. I was cleaned up and stitched at the hospital, heavily strapped and bandaged. The next day my Mum came up to take me back to London, where I remained unable to play for 7 weeks. During that time, Sandy Roberton arranged for an advance from RCA, for me as a solo artist. A regular visitor to my parents’ place that summer was Paul Scard; Paul (with Andy Rochford) had been Liverpool Scene’s roadie for the last few months of the band’s existence, and they were as keen as I was to continue our working relationship in the future. Bouncing ideas off Paul, I decided that I didn’t want to be a solo artist, but that I wanted to form a band to be called Everyone, to reflect the lack of a leader. Later on this was referred to as Andy Roberts with Everyone or sometimes Andy Roberts’s Everyone, but that was never my intention. I just wanted to be in a band, and I thought the name was a good one. I began writing songs for the first album. The first 2 were Ivy (Climbing Up A Castle Wall) and Don’t Go Down To The Ministry. These were both in the set when, at the end of July, Adrian Henri and I put together a band (which appeared under the name Liverpool Scene) for 3 dates in Norway. This was an old booking we couldn’t wriggle out of. We opened at the Sonia Henie Museum in Oslo, followed by 2 highly successful gigs at the Molde Jazz Festival. These were my first dates since the motor bike crash, and the band was myself, David Richards on bass, John Pearson on drums, with Alan Peters on trumpet and guitar. In a strange way this was a try out for Everyone, and it went very well indeed. Now, I had never led a band since I was at school in the early 60s: my university band, The Trip, already existed before I joined, and was a co-operative. So I had no experience at all. At first I had talked with people I knew around where my parents lived – Guy Price (bass with The Temeraires) and Nig King (drummer with The Blackjacks) both turned me down. Sandy Roberton had suggested David Richards from a band he already managed which was splitting – Paul Kent’s band P.C. Kent. Dave and I really hit it off in Norway, musically and personally. I had also by then approached John Pearson and John Porter. They were both acquaintances from touring days, and I rather idealistically thought that if the band were good friends then we’d play better musically. I quickly learned the error of that little theory! I decided I wanted a 5-piece, with a keyboard player. John Porter suggested Bob Sergeant, whose band Junco Partner was folding in Newcastle, and I offered Bob the gig on the basis of hearing their album. I had never met him at all, until we started rehearsing seriously in early August, in a rented house close to Stonehenge! Bob was a lovely bloke, a strong singer and writer with great experience, but we never found common ground musically until there were a few glimmers of understanding right at the end. “The day’s line up included two survivors from the 1969 event, the ever-present Gary Farr and “Everyone” – basically the Liverpool Scene without Adrian Henri – both of whom gave a good account of themselves.” AR: Well, not so good that they could tell the difference, apparently! Our London debut was at the Marquee, for which I lost my voice completely, so it was a disaster. We tried again at the Speakeasy, where someone spiked me, so I was away with the fairies. It all seemed doomed. The recording was difficult between Bob and me. I even gave him the vocal on my song Ivy in the hope that it would improve things, but it didn’t work and the song was shelved for ever. Before it even came out I knew it was all over the place, and I hated it. My first move was to change personnel. We lost John Porter (because I thought 2 guitars were cluttering the sound), but that made little substantive difference. It was tough, apart from the strengthening of my bond with David Richards. One night in November 1970 we played at Southampton University. Andy Rochford had copped off with a girl, and decided to stay down in Southampton. Paul Scard was fine with that, and he alone drove us back to London. I ended up at John Pearson’s flat in Bruton Place, with Paul as well, drinking tea, smoking dope, the usual. It was maybe 2am when Andy Rochford phoned, asking Paul to go back to Southampton to pick him and the girl up, as their place to stay had fallen through. Paul, bless him, didn’t hesitate to do as his mate requested. It was a cold night. Paul picked them up, and on the way back, in Basingstoke, a flatbed lorry hit a patch of ice, jackknifed going round a roundabout just ahead of them, and the trailer came scything round into our van. Andy and his girl were asleep, lying down on the seats; they were badly cut about, but Paul was upright, driving, and the trailer decapitated him. He was 19 years old. The first I heard about it was the following morning, at my parents’ house, when anxious friends of my Mum and Dad called up. It was in the Stop Press column in the Daily Telegraph (remember those?) that I had been killed. In all the wreckage they had found my guitar case with Liverpool Scene stenciled on it, and had assumed I was the victim. I have had to blank the aftermath, at least where Paul is concerned. I remember his funeral, and the financial chaos of losing the van and all our gear, but Sandy picked up the pieces for us. We hadn’t even finished the album before he died. I fulfilled all the outstanding dates I could, as an acoustic trio with Dave Richards on bass and John Pearson on congas and tablas. Once the gigs were over I went into a deep hole, as you can imagine. I have probably only ever seen Bob, or John Porter, a couple of times since then. The last time I saw Bob was at the launch, at the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios, of Ken Garner’s In Session Tonight – the definitive book on the John Peel sessions. That was in 1993. SHINDIG: An alternate version of the album includes your take on Neil Young’s ‘Cowgirl In The Sand.’ How did you come to choose that cover and did you have any problems securing the rights to record it? AR: Here’s how it works, Jeff. When he/she writes a song, the writer has the right of first usage; no-one can record it before the writer does, without his/her express permission. Once it is recorded, however, anyone can record it without any further need for permission from the author, as it is deemed to be in the public domain. All you must do, of course, is to pay the appropriate royalty due on the amount sold. So for instance anyone can record any Beatles song they wish to! Cowgirl In The Sand was a favourite late night jam for us during the Everyone rehearsals, and one day we recorded it at Sandy’s suggestion. It was not a track I would have wanted out in the UK, but after the demise of the band it was put on an album in Holland. It was already pressed before anyone told me. SHINDIG: Urban Cowboy seemed to take a long time to release, featuring recordings over a three year period from 1971-73. Was it difficult coming up with material for that album or were you just overwhelmed with outside activities? AR: Definitely the latter! Nina And The Dream Tree had been released in September 1971 to great acclaim. I had toured the US with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson that summer, and I returned for a solo tour to promote the Dream Tree album all through that autumn, supporting Steeleye Span (the new line-up with Martin Carthy). At the end of that tour, in December 1971, I had formulated the basis of Plainsong with Iain, and the whole of 1972 was taken up exclusively with that band, so I didn’t return to solo recording until early 1973. 2 of the tracks on Urban Cowboy are by Plainsong – the title song and All Around My Grandmother’s Floor. SHINDIG: Lots of old friends on this one, from Richard Thompson and Iain Matthews to Neil Innes and Martin Carthy and a return to writing with Mike Evans from hyour Liverpool Scene days. Do you look back with fondness on this one today? AR: I can see that it is pretty disjointed because of the 18 months between the first and last tracks, but it has some pretty strong material, and over all I was very happy with it, and I think it still has merit. The friends make it even more special. By the way, Grandmother’s Floor was written during the Liverpool Scene’s time together – according to Ken Garner a version was in our session for John Peel’s show Top Gear on 19th January 1969. That’s about 4½ years before Urban Cowboy was released! SHINDIG: Finally, The Great Stampede. Perhaps one of your strongest bands, featuring Gerry Conway and Pat Donaldson from Fotheringay, and some great contributions from Zoot Money and Ollie Halsall. How did you get along with Ollie? Was he as awe-inspiring as his legend makes him out or was he just as excitied to be working with you? AR: By August 1973 I had learned how to pick a band! These were all my greatest friends from my time as a session player, and I had the deepest respect for each and every one of them. Zoot Money is a genius. It was a fantastic experience to record that album – I loved it all, and it was the absolute best I could achieve at that time. The only wild card was Mick Kaminski. This was long before his time with the Electric Light Orchestra. Mick was playing with a band called Joe Soap, and Sandy had used him on other sessions and recommended him to me. I remember saying we’d use him on day one, and see how it went. He fitted right in, and it was a magic week recording the basic tracks. Ollie, I knew from Liverpool days. He had been the drummer with a band called The Music Students. Then the guitarist left the band and Ollie took over – within 6 months he was the best player on Merseyside. Probably the most awesomely talented guitarist I have ever met. I saw him with Patto from time to time in the late 60s. At the time of The Great Stampede he was still with his wife and children, living in Abbots Langley, not far from my first proper house in Bushey, and I would drop over from time to time. We had played together earlier in 1973 on Neil Innes’s first solo album, How Sweet To Be An Idiot. I’d say we were friends. But he only played on one track, Speedwell; all the other guitar playing is mine! We overdubbed Ollie at the old Livingston Studio in Barnet, after the basic tracks were finished at Olympic. SHINDIG: The reissue is now out with five bonus tracks. Can you tell us about them? AR: These were outtakes and curios I had in my personal collection. I would have left the reissued CD exactly as the vinyl had been, but I was overruled. So to add value the 5 extra tracks were added. The full details are in the booklet with the CD, and I can’t add to them, really. So here they are (slightly edited): Home at Last. Written during the year of Plainsong, but never, I think, performed by them. This was from a bunch of songs recorded with Neil Innes on piano and Hammond organ, and David Richards on bass, during the GRIMMS time in early 1973. Viv Stanshall and Neil had been friends of mine increasingly since I played with Bonzo Dog Freaks in 1970-1. David was my stalwart right hand man from 1970 onwards, into Plainsong and beyond. To not use him for the Great Stampede was a huge conscious decision, but we resumed for another 2 years with GRIMMS, and he remains a pal to this day. Originally this song was called Same Tune, Three Times. Makes sense to me. Lost Highway. Iain Matthews was largely responsible for introducing me to ‘classic’ country music – the kind I like. I was powerfully moved by the life and legend of Hank Williams, and I still am. Dead at age 29, alone, on the slide, full of booze and drugs in the back of a Cadillac on the way to a gig. Here, I’m trying on Hank’s voice, flat-toned, no vibrato. Not one of his own songs, but a great one nonetheless. Living In The Hills Zion. I had never heard of Marcus Garvey or Rastafarians before I went to Jamaica on honeymoon in May 1973. Went to see The Harder They Come. Saw that wonderful moment when the artist Ras Daniel Heartman rises from the ocean and shakes his locks. I have a sketch of his on the wall to this day. Anyway, we were told that, as a rule, true rastas liked to live apart from other people, in the hills of the interior, but there was a group who were approachable, living at a place called Cascade, above the beach at Negril. Negril today is a nightmare of hotels, but then it was a 7-mile long strand of white sand with no buildings at all, and deserted. Utterly enchanting. Jacqui and I hired a car, and drove there, dodging land crabs all the way. Found a sign to Cascade and started driving up, and up, and up. Eventually the stones blew a tyre, so we got out and walked. We found Booli at his house. There followed a magic day when we smoked herb, ate, swam, talked and shared. They took me to see their ganja fields deeper in the hills - acres of redtops, 8 feet tall. Lovely gentle spiritual people, far from society, self-sufficient, their only tools a ratchet knife and a machete. I looked Cascade up on the internet a few days ago. Now, it’s a golf course. The track has another outing on the rumba bass, and is a demo. I never recorded the song again. New Karenski. In the late summer of 1971 I toured the US in an acoustic trio with Iain Matthews and Richard Thompson. Iain was the star – he was newly signed to Mercury Records, so Richard and I roomed together all across America. This was before Richard became a Muslim, and calmed down. In Boston, at a club called the Poison Apple, I met Karen Goskowski. At that time I thought she could be the one. There was a slight problem – she was married, but living apart from her feller. Later on they sorted it out, and such is life. But my songs Poison Apple Lady, Urban Cowboy, and this one are about her. She worked for an airline, so could come to places as we played them, but she never made it to England. Sandy Koufax’s Tropicana, a motel on La Cienaga Boulevard in LA, was a favourite place to stay, ‘cause it was down the street from Doug Weston’s Troubadour club, where we played twice. The swimming pool had cracked in an earthquake and leaked all its water away. I think it was $12 a night. The air-conditioning didn’t work. It was there Richard and I met Don Everly, and Mo from the 3 Stooges. Later on it was Tom Waits’s home for a while. You get the picture. Having a Party. Zoot Money on Hammond, David Richards on bass, and John Halsey on drums. I first met ‘Admiral’ Halsey when he was playing in a talent contest at the Rhodes Hall in Bishops Stortford. I was there supporting a friend’s band from school. John’s band, Felder’s Orioles, won first prize. My lot came third. Later on he played with Ollie Halsall in Timebox, and Patto. Later still he was in GRIMMS, and the Rutles. He now manages the best pub in Cambridge. This is a reggae version of the Sam Cooke classic, the way I’d like to have done it at Dickie Wong’s club on the Red Hills Road. Zoot’s voice on the fadeout is sublime. SHINDIG: How would you rate this amongst all your other releases? Great Stampede? The best by far, but in an admittedly small field! AR: When I began to write for theatre in late 1973 I found something I liked more than making records, so I stopped trying to be a star. Good move – the records never made me a penny, the musicals still earn money today, not much, but still it’s real money. |

|---|