We thought the best way to recoed Andy's biography was to include a series of interviews over the years. |

|---|

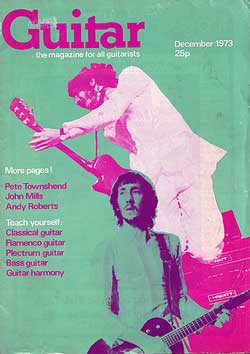

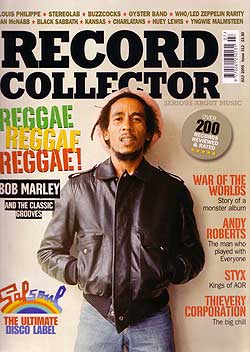

GUITAR MAGAZINE

1973

Andy Roberts Tells Jeffery Pike...

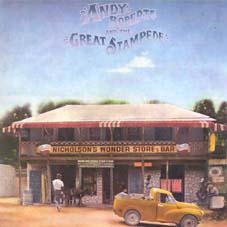

‘I’m a guitar junkie…’ Andy Roberts gets around. You may have seem him looning about with GRIMMs, the poetry/songs/sketches/rock/pantomine ensemble, or accompanying poets like Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten on acoustic guitar; or earlier work with Scaffold and the Liverpool Scene’ or co-leading that interesting but short-lived band Plainsong. He’s also made four albums under his own name, the first three featuring lots of acoustic guitar picking, the latest (Andy Roberts and the Great Stampede, just released) a bit heavier and more electric. I asked Andy if he set out deliberately to make a heavy record. ‘It’s not really heavy … it’s soft rock by any standards. But I know what you mean. ‘On my previous albums, because I was known mainly as a guitarist, there was always a feeling that there had to be fancy guitar picking in the middle of it all. When there was a band on it, it all fitted round the central guitar part. But this time I wanted to move on to al slightly different sound. Also, I knew I’d be working up until Christmas with GRIMMS, which includes, amongst other things, a rock band. So I knew this was how I was going to promote the album, and you can’t promote a folk album with a rock band.’ The current GRIMMS tour contains the mixture much as before – poems, sketches, funny songs, straight rock and roll. Was Andy happier working in that context than being on the road with a simple rock band? “That band, on the record, I would never be able to put on the road: the economics of working a band are really silly. The economics of GRIMMS are even sillier, but we only do it now and then. It takes an awful lot of planning beforehand, it’s a big team: there‘s about 15 on the road, so we have to get as much work as possible in a short time to make it work. I don’t really want to front an Andy Roberts band. But it’s lovely working with the GRIMMS band, juts being a rhythm guitarist for one of Zoot’s sub-soul songs, or being silly on one of Neil’s (Innes) funny numbers. There’s an enormous amount of scope. With so much scope in his music-making, it’s not surprising that And has a large collection of guitars. “Yeah. Lots and lots. I’m a guitar junkie. On the road I just take whatever guitar I feel like at the time. My electric guitar is usually a Fender Telecaster or a Gretsch County Club. They’re two very different things. The Gretsch is sort of half-way between a Fender and a Gibby: you can get a very fat heavy sustain like a Gibson, but you can also get a very hard clipped treble like a Fender. The acoustics that I use are a Giuld D50, seven or eight years old, which is very loud, it’s a very big sound, and a Gibson Dove which I’ve had for some time. Doves aren’t always very good, but I took the top down on this one, took all the original finish off and French polished it, and now its got a very good sound, with lots of harmonics. I’ve got a 12-string made by John Le Voi. It’s very funny looking, but it’s a great guitar. It’s small-bodied but deep, and not very waisted; and the head is raked back quite sharply, it has a sort of lute angle to it. I’ve also got an instrument called a Kriwaczek string organ, made by a friend of mine Paul Kriwaczek, who’s a television producer, amongst other things. It looks like a steel guitar, and has six strings tuned a whole tome apart. They’re raised across the neck and the frets are raised to just below where the strings are. You play it with both hands, pushing the strings down to the frets. It has a pick-up, like a guitar pick-up and the actual vibration for the strings is generated by an eletro-magnet. The lovely thing about it is that it’s touch-sensitive. If you just press the string down ever so gently, it will start from nothing ans as the magnet gets a grip on the string it will roar up to a certain volume and sustain there until you release the string. But if you hammer the string onto the fret you get a very heavy percussive attack, then it will settle down to that constant. It’s a lovely instrument. I’ve used it on a number of things, with Scaffold, on Cat Stevens’ Teaser and the Firecat album, and so on. But I can’t really play it, I’ve never fully developed it in the way I’d like to. The trouble is, when you’re a guitarist, with a living to earn, you don’t really have a lot of time to devote to other things. Whish is very hard on Paul. There’s this beautiful instrument and no one to use it properly. It’s an instrument without a player, rather like the gob-harp before Larry Adler came along. ‘I’ve got a dulcimer too. That was made in the Santa Monica dulcimer works in Los Angeles. I didn’t know the first thing about dulcimers. I’d hardly ever seen one before. The man who made it sold it to me when I was very drunk in the Troubador, a couple of years ago. I woke up the next morning and found I was a few dollars lighter and a dulcimer to the good. So I set about teaching myself to play, and I love it. It’s a beautiful instrument. I just strum it: the really good players like Howie Mitchell are right out of my league.’ Andy also plays violin – or rather, he did play the violin very well until the guitar took over. ‘I’ve still got the fiddle, but I very rarely use it on stage. I got quite good when I was studying it, but I stopped playing it in ‘64 or ’65, and since then … it’s gone. When you stop playing seriously, it’s one of those instruments were your technique disappears very quickly.’ So why did he turn to guitar? Because it was more glamorous? ‘Partly, yes. Had I been born ten years later, I might have stuck with the fiddle and not bothered with the guitar. But in those days the fiddle as very unfashionable. But besides that, the guitar is polyphonic. You can’t play chords on with a fiddle. I’d been brought up in a classical music tradition, so I had no grounding in improvisation of any kind. I was only equipped to play other people’s dots. At first, I could play practically nothing on the guitar, but everything I could play was all mine. I wanted to create, and I couldn’t create on the fiddle. ‘I went through the thing of playing in Shadows bands and learning all the licks, then I went through the rhythm and blues thing, fooling about with bands at school. I left school in 1964 and played in a band called Blues en Noir, a rhythm and blues band. Then the next year I got a place at Liverpool University to read Law. I had a typical Londoner’s reaction to Liverpool in those days – God, it’s full of fantastic bands, I’ll never be able to get a place in a band in Liverpool. So I just jacked in all the electric playing and bought myself a Hoyer 6-string. That wasn’t a very good 6-string so I had two extra machine heads fitted and made it an 8-string with octave strings on the third and fourth. ‘That was an idea I copied from my first big guitar hero, Spider John Koerner. He played seven-string guitar in fact. I got my first John Koerner album in 1965, and I played him incessantly, I copied him, I wanted to learn all his songs, I just wanted to be another Spider John Koerner. That was when I learned to play with fingerpicks. I can’t remember working very hard at it, but I probably did, because within two months I was very proficient at that syncopated ragtime-type picking. More so that I am now, because I don’t do it so much. Anyway he was my first and greatest guitar hero. Of course, when I got involved with the poets and Scaffold, the whole Liverpool Scene thing, I was in the situation of creating for myself, so naturally I moved away from copying somebody else’s style and found that I was creating one of my own.’ Andy was one of the first people in Britain to use the acoustic guitar as an accompaniment to poetry readings. It’s a difficult art, and he had to work hard at it: ‘It took a long time to discover how to reach an equilibrium between the guitar and the poem. For along time I felt that the guitar always had to be subordinate; I wanted to create a carpet for the poem to walk on. But there wasn’t any furniture on the carpet. Then when Adrian (Henri) and I got closer, he related to the fact that I was there beside him. We’ve now (Adrian passed away in 2000) reached a situation where the poem is adapted and woven round the music by Adrian in exactly the same way as music is woven round the poem. That’s the really nice thing If I want to go off in a different direction, he’ll often improvise sections of the poem, or extend them, to fit them in. That only really happened with Adrian: he’s the musician amongst the poets I work with. Roger McGough’s poems are more wordy, and he’s very metrical, so you can fit a more rigid rhythmic frame-work to them. Brian Patten is different again; he’s totally unmusical, so you’re really working with him in spite of it. He doesn’t seem to take any notice of the guitar! Is pace is different from night to night – as he feels it, he does it. So you have to work very much to him. But that’s nice in some ways, it’s an interesting thing to do.’ As he said, working in unconventional (for a guitarist) surrounding has forced Andy to develop his own guitar style of guitar playing. But he still listens hard to other guitarists: ‘I’m very susceptible to influences. I could probably name a dozen people who have influenced me in some way over the past five years, either in terms of writing or playing, on both acoustic and electric guitar. I was always knocked out by Roy Harper as an acoustic guitarist. He has had a very bad press, but to me he is amazingly good. Jerry Reed is another favourite. On electric guitar, for a time I got very heavily into Merle Haggard’s lead guitarist Roy Nichols, who is superlative. I love the way he plays. ‘Then there are people I admire and listen to, but I don’t really lift anything from them. In England, Richard Thompson is way out on his own: there’s no one to touch him in many ways. Tim Renwick is a fine player. Ollie Halsall is superb; he’s one of the few people I know who’s really humorous. He’s got all the technique, but he’s just unbelievably funny as well. Jerry Donahue has come on really well: his country stuff is amazing. I don’t copy people now. But people that you listen to for the sheer pleasure of listening and enjoying, you naturally assimilate an amount of their feel or their basic approach. I try to keep my role in perspective with regard to other people: there’s always someone who’s much better than yourself. That’s one of the basic laws of the game.’

|

|---|

It’s a solid-sounding band, there’s lots of instrumentation on it. That was just the result of the people I chose to play on the session really. The same six people did most of it: Gerry Conway on drums, Pat Donaldson on bass, Zoot Money on piano, BJ Cole on steel guitar and Dobro, Mik Kaminski on electric fiddle and myself on electric guitar. I play acoustic on a couple of tracks, but just strum through the number. There’s virtually on acoustic guitar picking as such.

It’s a solid-sounding band, there’s lots of instrumentation on it. That was just the result of the people I chose to play on the session really. The same six people did most of it: Gerry Conway on drums, Pat Donaldson on bass, Zoot Money on piano, BJ Cole on steel guitar and Dobro, Mik Kaminski on electric fiddle and myself on electric guitar. I play acoustic on a couple of tracks, but just strum through the number. There’s virtually on acoustic guitar picking as such.